Here’s

a train where you need no ticket...

Hannah is waiting

By

Tom

Conoboy

Jamie

Forbes shuddered awake as the train went over a set of points. He tried to

focus on a poster about security. He concentrated on not being sick. He couldn’t

remember getting drunk, so why did he feel like he was circling the carriage

like a balloon in a draught? More to the point, what was he doing on a train

anyway? Why was he not back at the garrison, asleep in his bunk?

“Meeting

Hannah,” he thought.

Who

was Hannah?

There

was a man seated opposite him, a minister, looking away, feigning an interest

in the blackness beyond the window. He appeared keen not to have to minister to

the drunken squaddie beside him.

“Penny

for your thoughts,” said Jamie.

The

minister looked up and applied his professional, smiling demeanour. “A penny

for the black babies,” he replied.

Jamie

was confused. I’ve gone awol, he thought. That’s a court martial offence. What

did he say? Black babies?

“What?”

“Penny

for the black babies. Do a good deed. Help a heathen today.” He had a soft

Irish accent, the sort which dispenses with extraneous consonants and makes

everything sound like a lullaby.

Jamie

looked around but they were alone. He shook his head, regretting it as the

carriage began to spin. A couple of miles rolled by and the dark outside seemed

to get blacker. We must be in the country or something, Jamie thought.

“Why

did you say ‘penny for the black babies’?”

“I

didn’t, did I?” The minister paused. “Yes I did. How curious. Why do you think

I said that?”

Jamie

no longer felt drunk. He wasn’t sure what he did feel, it was like no sensation

he had ever known. The nearest was at that camp in the Brecon Beacons when they

only had three hours rest and as he started to wake up he dreamed that he was

falling asleep, and his brain began to argue with itself but didn’t know why.

“I’m

sorry,” he said. “I’m having enough difficulty keeping track of what I mean,

let alone you. You’re on your own, mate.”

The

minister nodded as though Jamie had said something profound. His fingertips

were pyramided together. “Yes,” he replied. “You do seem to be saying some

peculiar things.”

“Am

I? Like what?”

“‘The

sky’s on fire and I must go’ was one. ‘Happy in the arms of my baby.’”

“I

said that? When?”

“Just

now. Oh dear, something keeps coming back to me. Save the black babies that

didn’t need saving anyway. Ignore the white ones that do.” He paused for a

moment. “I doubt you’ll have reached it yet, but you get to a stage in your

life when all that’s left is regret.”

Jamie

nodded. “Hannah deserves better,” he said.

“Who’s

Hannah?”

“I

don’t remember.” Jamie shrugged his shoulders. The two men stared at one

another. They were glad not to be alone.

“It’s

the illusion of doing good, you see. Helping the uneducated in far off places.

Saving them for the Lord. As if they wanted saving. Or needed it. But it was

much easier than helping the wretches on your own doorstep. More exciting, too.

Do you know what I mean?”

“I

quite like me own doorstep, to be honest mate. Peace and quiet, home cooking,

somebody to cuddle up to. Better than all that bloody dust and heat in Iraq,

anyway.”

“Have

you been in Iraq?”

“Been

on duty with the Black Watch, yeah. Basra.”

“Somalia.”

“You

what?”

“My

ministry. I was in Somalia. Doing God’s work.”

“You

and me both, mate.”

“Does

he see it like that, do you think?”

“How

would I know? Just do what I’m told, me.”

The

minister wiped his hand over the window. There was no light to be seen.

“Are

we in a tunnel or something?” said Jamie.

“Perhaps.”

“It’s

seems a long way to Birmingham.”

“It

is from here, you’re right. I’m Father Mahoney, by the way.”

“Pleased

to meet you. Jamie.”

Father

Mahoney smiled. He seemed like an okay sort of guy, thought Jamie. For a padre.

“So,

you just back from Somalia then?”

“Oh

lord, no. That was thirty years ago. I’m just an ordinary minister, now.”

“Don’t

have much time for religion, no offence. Don’t believe in it.”

“Me

neither.”

Each

looked as surprised as the other by this confession. There was an uncomfortable

silence. “So where do you padre now?”

Father

Mahoney laughed. “The funny thing is, I don’t know. Isn’t that silly? I can

remember everything from thirty years ago, but I don’t know what I did

yesterday.”

“I’m

the other way round. I can remember yesterday, but nothing before that.”

“Hannah?”

“Exactly.”

“So

tell me about yesterday.”

Jamie

shivered. He shook his head. He looked outside the carriage.

“I

understand,” said Father Mahoney.

“Do

you?”

“Not

really. I’m just trained to say that.” The two men laughed. They let silence

fill the void. It no longer felt uncomfortable.

“So

did you save many, then? Black babies?”

“Hardly

any, I don’t suppose. I gave them God, if that’s what you mean. Might have even

given some of them hope, if it’s not too arrogant of me to assume that.”

“You

don’t seem like an arrogant guy.”

“No?

God sees behind the mask, my friend.”

“Don’t

suppose you believe that, neither?”

“No.

But I can see behind it. And that’s even more frightening.”

“You

must have done some good?”

“Yes,

I expect I did. We organised polio immunisations in the remote villages. That

probably saved a few lives.”

“More

than a few, probably. What about education?”

“Yes,

that too. We set up a school. But so what? I taught a few darkies to read. I

hardly changed the world, did I?”

“Was

you wanting to change the world?”

“When

I was your age, yes. Don’t you?”

“Not

me, mate. I just want to do my seven years and get out, start a family.”

“That’s

a very shallow way of thinking, if you don’t mind me saying.”

“At

least I’m not preaching to folks about a God I don’t believe in.”

“Touché.

I suppose I could respond by saying I don’t shoot people.”

“Me

neither. Never killed anything in my life.” Jamie stopped. His mouth twitched. He

stared across at an empty seat for some moments.

“Are

you okay?”

Jamie

looked at the minister. “I’m feeling a bit funny, to be honest. Are you

starting to remember things, too?”

Father

Mahoney nodded. “Slowly. Talking helps, I think. Carry on.”

“I

never wanted to be a soldier, not really. I were rubbish at school, only good

at sports and the like. Careers master suggested it. It didn’t seem too bad an

idea at the time.”

“Now?”

“Hate

it. Been in five years, now. Been in Kosovo, Ireland, Iraq. It’s all the

fucking same, wherever you go. You’re trying to help these people, and the

bastards just want to kill you.”

“Sounds

just like ministry.” Father Mahoney laughed.

“’Cept

you don’t get fucking shot at, do you?”

“No,

I was being flippant. I apologise.”

“You

got family, padre?”

“No.

I had a brother, died when he was a boy. And you?”

“Yeah,

lots, I think. I’m trying to remember.”

“Hannah?”

“Hannah.”

“Your

wife?”

“I

think so.”

“I

expect she loves you very much.”

“I

think so.”

“She

must miss you when you’re on duty. Worry about you.”

“I

think so.”

Jamie

felt a tear slide down his cheek. He was sure he had never cried before. Men

didn’t. Strangely, he didn’t feel ashamed.

Father

Mahoney nodded. “I feel like that, too. Don’t know why.”

“Can

you remember yesterday yet?”

“Not

all of it, I don’t think.”

“Something

happened though, didn’t it?”

Father

Mahoney’s hands were gripping his knees. He was looking at Jamie, but Jamie had

the feeling he was seeing something else. The Father nodded. “Marjorie

Bartlett,” he said. “One of my parishioners. Fine woman, in her eighties. She

never really liked me, hated the Irish, but didn’t let that interfere with her

faith. I admired that. She took Holy Communion every week.”

“Took?”

“She

died yesterday, in her sleep. She had emphysema. She found life harder and

harder. In the end, it got too much.”

“You

must deal with a lot of death.”

“You

and me both, I expect.”

The

lights in the carriage flickered and went out for a few seconds, leaving the

men in darkness. The air felt heavy and stale, hot and humid. When the lights

returned, both men were staring out of the window, watching a haze of light,

many miles distant, the only sign of existence in an expanse of black.

“Is

that Birmingham?” said Jamie.

They

travelled in silence for some minutes. Both wished to listen, but neither was

prepared to talk. The carriage grew hotter. Father Mahoney pulled at his dog

collar, sliding his finger between it and his neck. “Are you ready to tell me

about yesterday yet?” he said.

“We

were out on patrol, near our HQ. There was a lot of unrest because of the

Palestinian elections. We heard a couple of bombs go off, back near the

compound and started to head back. Suddenly, some bastard throws a grenade at

us. Before we knew what was happening, there were hundreds of them. Petrol

bombs, grenades, stones. I was the driver, tried to get us back to base but a

bomb hit us, knocked us sideways.”

“Wattie

was next to me. Got some shrapnel in the skull. Dead instantly. Doug was in the

back, he was on fire, screaming like fuck. The others covered, I dragged him

out, rolled him on the ground, threw a blanket on him. Poor bastard. Fucking

face melted away, this eye staring at me, his hand gripping mine so hard it

hurt.

“You

know what I thought about then? It’s weird, makes no sense. I thought about

when I was a kid, the first time I went to Bramall Lane to see the Blades. My

mate’s dying in front of me and I’m thinking about when I was ten, going to the

football with me da.”

“It’s

a stress reaction, my son.”

“He

couldn’t really speak, poor bastard. As well as the burns, he was bleeding all

over, shrapnel had hit him too. He had no fucking chance, I just held him.

Wanted to stroke his arm, touch him, do something to make him know I loved him,

but what could I do? He was burned everywhere.”

“I

suspect he knew.”

“Aye?

You weren’t there though, were you padre?”

“No,

my son.”

“You

bastards never are when it all kicks off. You piss off back to your chapels and

pray for calm and leave it to us to sort out your fucking mess for you.”

“I

wish I could argue with you.”

“So

do I. You’re all the same, you lot. You spout all this bollocks but whenever

anyone disagrees with you, you just smile and say ‘I respect your point of

view. God still loves you.’ As if that’s okay. At least the Arabs stand up for

what they believe in.”

Jamie

tried to stand but the carriage began spinning again and he slumped back in his

seat. “Of course, you get dispensation padre, since you don’t believe anyway.”

“Do

you imagine that makes it any easier?”

“D’you

think I care?”

“What

happened to your friend, Jamie?”

“I

don’t know.” Father Mahoney raised an eyebrow. “I don’t remember. Everything

stops just after that. I don’t remember anything.”

Outside,

the distant glow seemed brighter but no nearer. Both men stared at it,

wondering at its blueness.

“Why

is it that you’ve never killed anyone, Jamie? A soldier, in wartime, you might

say it’s unusual. Is it deliberate, or have you been lucky?”

Jamie

stared at the old man and closed his eyes for some moments. “It’s been the

hardest thing,” he replied. “It don’t do in the army to think those sorts of

things, but, you know, some of the things I’ve seen, padre. They make you

think. I watched a bloke die a couple of years ago, Arab guy, when we first

took Basra. He was lying in the street, shot in the gut, nobody could get to

him for the crossfire. He just died, slowly, while we all carried on shooting

at each other. And I thought ‘what the fuck?’”

“So

it’s deliberate, then? You’re a pacifist?”

“Yes.”

“Thank

you for telling me that. It couldn’t have been easy.”

“No.”

Jamie’s back was beginning to ache, at the base of his spine. He wanted to get

up and stretch but he was finding it difficult to move. The heat in the

carriage was beginning to make him feel sick again. He wanted a drink.

“What

about you, padre? You killed anyone?” He said it lightly but was surprised by

the old man’s silence. He scrutinised his face, tried to read it, but a

lifetime of ministry had masked it with blankness.

“Only

once. Twice, I suppose.” Jamie was staring at him, but he couldn’t return his

gaze. Instead, he looked at the floor. “Yesterday.”

“Yesterday?”

said Jamie, the pitch of his voice rising in surprise. “What? The old woman?”

Father

Mahoney nodded. “Marjorie. She was in such pain. She was so unhappy. She begged

me. For weeks, she begged me. Yesterday, she was in tears, in agony. I gave her

extreme unction, held her hand, and pressed a pillow to her face. Even though

she wanted me to do it, her body fought against it, as hard as it could. I felt

her struggling. I almost stopped, thought it was her soul fighting to save her

life.” He stopped speaking.

“But?”

“But

while I debated it, whether it was her soul or not, she died anyway.”

“I’m

sorry, padre.”

“Me

too, son.”

The

two men cried openly, each for the other. Jamie felt his back pain increasing,

spreading to his neck and legs. His hands were shaking.

“Twice,

you said.”

“Yes.”

“Why

twice? Who else?”

For

the first time in several minutes, Father Mahoney looked into the young man’s

eyes. “Oh Jamie,” he said, “do you not understand? Don’t you realise?” Jamie

shook his head, bemused. “You poor boy, you poor boy.”

“What?”

“Yesterday,

Jamie. You were surrounded weren’t you? By hundreds of them? With petrol bombs,

everything?” Jamie nodded, his eyes wide. “How do you think you could have got

out of there?”

“I

don’t know. The rest of the battalion must have come and got us. Rescued us.”

But,

already, Jamie’s voice was faltering.

“I’m

sorry, my son. There’s nothing I can say.”

Jamie

stretched in his seat, looked out of the window into the blackness beyond,

looking for the distant light, but it was nowhere to be seen. An image of a

woman, young and handsome, laughing and waving, filled his mind. Hannah, he

thought, and smiled.

“D’you

know where we’re going?” he said.

“No,

my son. I only wish I did.”

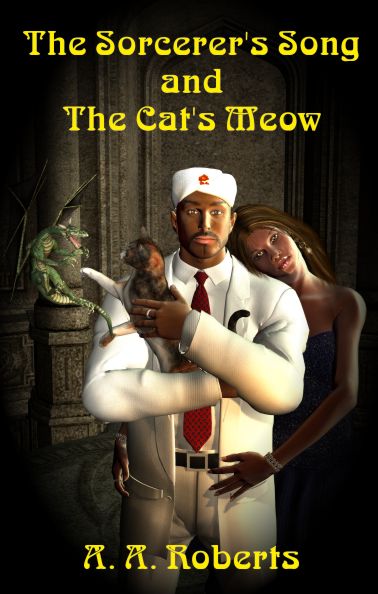

A cat and her sorcerer, a beautiful dream weaver, an evil voodoo priest,

a bunch of man-sized rats, an army of really big bugs, a crazed randy rabbit,

some dwarves, dragons and angry three-toed sloths, New York City, the woods of Maine,

the sands of Arabia and the mythic lands of Avalon all come together for the wildest

most epic adventure you’ve ever read!!!!

A cat and her sorcerer, a beautiful dream weaver, an evil voodoo priest,

a bunch of man-sized rats, an army of really big bugs, a crazed randy rabbit,

some dwarves, dragons and angry three-toed sloths, New York City, the woods of Maine,

the sands of Arabia and the mythic lands of Avalon all come together for the wildest

most epic adventure you’ve ever read!!!! The Sorcerer's Song and The Cat's Meow is an author's triumph and a reader's delight... What a wonderful, free-falling storytelling ride to get to the end of a fantasy that's about as close to purrfect as you can get.

M. Wayne Cunningham - ForeWord CLARION Reviews

A well-plotted story with vivid and riveting description of characters and settings, as well as an intense page turning battle, the book is a delight to read.

Tracy Roberts - Write Field Services