If OSHA only knew…

The Inspector

by

Chris Clark

In the last days of summer, when the heat from

the three suns had become nearly unbearable and the constant tattoo of

deep-throated drums echoed from the forest, an Inspector came to the refinery. The announcement of his arrival made an

already frustrating season even more difficult, as mandatory overtime schedules

were imposed and leisure passes revoked in an effort to prepare the mines and

the massive refinery for the impending visit.

Managers stalked the plant, supervising the workers as they cleaned and

re-cleaned every bit of machinery. Grime

that hadn’t been touched in the decade since the last inspection was

scrupulously removed, and fresh paint was applied to walkways and walls.

During the entire run-up to the inspection,

while men worked twenty hour days and the mood steadily degenerated, the drums

beat relentlessly, sometimes in a steady, monotonous rhythm, other times in a

random cacophony. The drums were there

no matter where one went in the plant: even in the mines, which by now

stretched three kilometers into the planet’s interior, the mine rats swore they

could hear the drums.

The Inspector’s visit

made life difficult for everyone at the refinery, from Plant Manager Borla down

to the lowest menial worker. But for men

like Tom Parker, Ed Kolowinski, and Skinner Bowie, the timing of the inspection

was intolerable. All three men were

within three months of fulfilling their five-year contracts and receiving

sizeable bonuses. The idea that the

Inspector could revoke all five-years if the plant didn’t pass muster was

impossible not to dwell on.

“I’m telling you, I

knew a fellow who spent eight years on Spirco Four and lost his bonus two days

before his contract was up.” Parker

stopped talking and glared around the table as if daring anyone to contradict

him. No one looked likely to do so:

Parker stood well over two meters tall, with a barrel chest and arms and a slab

face. “The Inspector said that safety

procedures weren’t being followed, and the Company iced all the contracts. They said it ‘wouldn’t do to reward employees

for following unsafe practices’. Eight

years and he loses his bonus like that.

Even if Spirco is a vacation compared to this place, it was still a

lousy thing to happen. You mark my

words, the Company’s going to try the same thing here.” This announcement was greeted with an uneasy

silence by the men sitting around the table.

Ed Kolowinski caught

Bowie’s eye across the table and raised an eyebrow in silent query. Out of all the men currently stationed at the

plant, Skinner Bowie was the one person Ed trusted to think things carefully

before reaching an opinion. If Skinner

said something, it was probably true. Ed

felt as uneasy as everyone else at the thought of losing his bonus at this late

stage, but he wasn’t going to worry too much about it until he got Skinner’s

take on it. Unfortunately, Bowie’s only

immediate reaction was to shrug his shoulders and look away. No help there, apparently.

As his drinking

partners sat and brooded over their mugs, Kolowinski leaned back in his chair

and looked around the tavern. Faced with

a workforce on the edge of open mutiny after weeks of twenty hour days,

management had granted one night of leave after only ten hours of work; it

looked like most of the plant was taking advantage of it. The room was packed to overflowing: there

must have been nearly a thousand men packed into a space meant for a crowd a

third that large. Large groups sat

packed around tables, men sat elbow to elbow down the long bar at the far end

of the room, and hundreds of others simply sat on the floor, drinking and

enjoying a few moments of companionship after the long weeks of non-stop

work. The room was far quieter than Ed

would have expected. Raucous laughter filled

a few tables, but most of the patrons were somber, focused on drinking and the

threat of the upcoming inspection. Even

here, in the depths of the plant, the drums were audible. Until a moment ago Ed hadn’t been consciously

aware of them, but now that he had noticed them he couldn’t get his mind off

them. They stayed on the edge of

awareness all the time now.

“They wouldn’t do

that, would they, Tom? They couldn’t,

could they? What about the contracts we

signed?” The speaker was a man named

Walters who Ed only knew vaguely.

Walters was a small, spindly man with a pinched face and a whiny

voice. Ed joined the rest of their table

in hooting derisively at the question.

Parker just stared stonily at the man before responding.

“Of course they

would. You think the Company cares about

you? You think because you signed some

piece of paper, the Company has to honor it?

Why do you think the contracts are on paper in the first place? Because that way there are no permanent

records of the damned things, that’s why.”

Parker laughed bitterly before continuing. “They can do whatever they want, and there’s

not a thing we can do about it.”

For a moment Walters

looked like he was going to argue the point, but then his face fell and he

downed the rest of his beer before standing up and weaving his way unsteadily

to the door. Someone kicked his chair

out of the way and the men shifted their chairs to fill in the empty spot. The rest of the evening was spent drinking

and trying not to listen to the rhythm of the drums coming up through the

floor.

The Inspector was

scheduled to arrive one week later, during the evening hours of Third Day. Only Deuce, the smallest of the three suns,

was currently visible, but the weather was still brutally hot and humid. Management must have regretted giving the

workers that night off, because since that time they had been driven even more

relentlessly.

Kolowinski stood in

front of the plant with Skinner and Parker, sweating in his freshly pressed

uniform and trying to ignore the dull ache in his back and legs. The entire plant staff was turned out to

greet the Inspector. Mixed among the

workers were numerous security officers dressed in the same gray coveralls as

everyone else; their presence, Kolowinski thought grimly, was probably all that

was preventing a mutiny at that point.

After countless hundred-hour weeks, asking the exhausted workers to

stand at attention in the hundred-degree heat for two or more hours while the

drums echoed into the clearing seemed like a sure recipe for disaster. The drums were particularly random at this

moment: there was no recurring rhythm or pattern at all that Ed could

discern. A mix of drums in a wide tonal

range sounded in a cacophony of frenzied beating. Every time he thought he had gotten used to

the drums, the natives found a new way to drive him crazy. He could see more and more men shifting and

looking around angrily; the tension was building by the minute. An angry buzz of grumbled complaints was

growing incrementally.

“Hey Skinner, what do

you think? A fifty says there’s a riot

if he doesn’t get here in the next twenty minutes.” Before Skinner could respond, a fist fight

broke out between two men ten yards away from Ed and his friends. The crowd started to shout and circle around

the two men, but before they could move far, two men in the crowd moved forward

quickly, pulled taser batons from inside their clothing, and subdued the

fighters. Everyone else scattered as the

men donned security helmets that they seemed to procure from thin air. The two workers started to protest

frantically as the security officers marched them toward the plant gates.

Skinner turned to him

with a wry smile. “I don’t believe I’m

going to take you up on that wager, Ed.”

He turned to look at the management team, standing a short distance from

the laborers and scanning the skies nervously.

“I would, however, bet that Plant Manager Borla is going to wet himself

if the Inspector doesn’t arrive soon.”

Ed just shook his head

as Parker and a few others chuckled and turned to look admiringly at

Skinner. That was Skinner for you: if

anyone else had dared to make that comment, there would have been half a dozen

Security goons waiting to pounce. But

Skinner never seemed to worry about Security, even though he criticized

management more than anyone Ed knew.

Before Ed could think

of a response to Skinner’s comment, he saw the managers pointing. He joined the rest of the crowd in looking in

the sky to the north. Deuce was hanging

fairly low in the western sky by that point, but he could see nothing in the

deep blue of the sky. Some of his

coworkers were pointing now, but he still couldn’t see anything.

After another couple

of minutes of this, he finally saw the Inspector’s car approaching out of the

northern sky. As the craft approached

the plant a silence descended over the crowd, all restlessness now gone,

replaced by awe or fear. Ed stood

silently with everyone else as the car made its final approach.

The car – really a

space-to-ground shuttle, of course, but

always referred to as a ‘car’ for reasons Ed had never figured out – was

absolutely silent as it descended gently to the ground and landed with absolute

precision. The craft was easily ten

meters long, a matte-black tube with a flattened lower surface, unbroken by any

signs of windows or doors.

After the car touched

down nothing happened for five long minutes.

At first the management team stood at attention, but after a couple of

minutes they started to shift around and look at each other uncertainly. Borla tried a reassuring smile, but to

Kolowinski he looked scared half to death.

The laborers started to mutter nervously, a low-pitched counterpoint to

the drums that were still echoing across the clearing.

All at once the drums switched

from random noise to a single slow, steady, ominous beat. Concentrated into a single, relentless

rhythm, the sound of the drums was an overwhelming pressure in Kolowinski’s

chest. Despite himself, he felt a strong

urge to hide somewhere, anywhere that wasn’t out in the open. After two minutes of this, the door of the

car slid upward without warning. The

Inspector stepped from the car and into the fading light.

Kolowinski’s immediate

reaction to his first glimpse of the Inspector was extreme dislike. The man was tall and extremely thin. Dark, expensive-looking sunglasses hid eyes

set in a pale, aristocratic face already wearing a look of prim distaste,

topped by close-cropped, immaculate dark hair.

He was wearing a dazzling white suit that Ed didn’t give a snowball’s

chance of staying white once he stepped foot inside the refinery.

The Inspector had only

taken a couple of steps forward when he stopped suddenly and stood absolutely

still with his head cocked to one side.

Plant Manager Borla, who had started forward to offer a much-rehearsed

welcome speech, faltered to a stop and looked at his aides uncertainly. Clearly unsure of what to do next, the plant

manager settled for standing and waiting for the Inspector to move again. Kolowinski thought he could figure out what

was happening, even if Borla seemed clueless: hearing the drums for the first

time had to be a disconcerting experience for anyone, let alone for someone who

apparently valued quiet order as much as this Inspector was supposed to.

After standing

stock-still for a good minute, the Inspector moved forward with a start and

strode with short, decisive strides past Borla, who was again trying to stammer

out a greeting, and toward the open main gates of the refinery. The laborers scrambled to move out of his way

as he walked straight through their ranks as though they weren’t even

there. Followed by a dozen attendants,

he walked into the dark maw of the refinery gates and disappeared from view.

None of the

rank-and-file workers saw the Inspector for the next three days, although the

constant pressure to increase production and follow safety protocols to the

letter was all the reminder of his presence they needed. Borla had reinstated the standard

twelve-hour, six-day work week, but it seemed to Kolowinski that the line

foremen were determined to make up for the lost man-hours by pushing everyone

to work twice as hard. Ed all but forgot

about the inspection over the next few days as he worked until he was ready to

drop each night before dragging himself off to his bunk.

When the Inspector did

reappear, the tension level in the plant rose even higher. The Inspector moved from station to station

relentlessly, examining machinery, interviewing workers, and inspecting the

refined ore with merciless precision. No

detail was too small to escape his attention.

He took notes constantly, whispering into a recording chip surgically

implanted in his wrist and instructing his aides to compile thousands of digital

pictures and videos. Amazingly, the white

suit never received so much as a smudge, in a plant where most of the

employees’ hands were permanently stained black. Everywhere he went workers all but stopped

breathing from fear.

The drums never relented

once during the inspection. Workers

stationed in the outer parts of plant, closest to the walls, could hear as many

as twenty differently-voiced drums at once, constantly varying in rhythm,

pitch, and intensity. For those workers

stationed deeper in the plant, the sound was lower-voiced, with less variations

getting through, but the sheer monotony of the noise was almost worse for them

than for those who could at least hear some variety in the noise. The unfortunate laborers assigned to tasks in

the mines themselves, the mine rats, were subjected to the constant pounding of

the deepest drums, a sound so low and intense it was felt as much as heard.

At first, the

Inspector didn’t seem to notice the drums, or if he did he was able to ignore

them. To the men he was inspecting, who

had a hard time ignoring the drums even after living with them for months, this

was a feat bordering on the supernatural that only served to heighten their

fear of him. His focus never faltered,

his intensity never wavered, even as nervous laborers stammered through carefully

rehearsed answers to his questions and tried to stand up under his icy stare.

After a few days of

this, Ed found himself back in the bar, sitting at a corner table with Tom

Parker and Skinner Bowie. All three men

were exhausted and emotionally spent, but the prospect of skulking back to

their bunks again was unbearable. They

didn’t talk much at first, content to sit and nurse their beers. Finally, Parker broke the silence.

“I hear tell he isn’t

even fully human anymore, not the way we are.

Johnson over in Sorting told me that the Company does brain surgery on

the Inspectors to make them smarter and meaner than regular people. He says they don’t even need to eat or sleep

anymore, so they can spend all their time inspecting stuff and looking for

reasons to fire people and shut down plants.”

Parker nodded his head decisively after saying this, like he had proved

a telling point. Bowie just shook his

head in disgust.

“Johnson in Sorting

would need brain surgery to achieve the intelligence of the average lump of

coal. The Company wouldn’t spend the

money to alter their Inspectors like that.

They just recruit people who are already mean as sin, that’s all.” Bowie stopped and drained half his beer before

continuing. “Besides, I don’t think our

Inspector is quite as steely as he’d like us to think.”

“What’re you talking

about, Bowie?” Tom asked

indignantly. “I had to explain my

station to him and I thought he was going to rip my heart out of my body right

there. I’m telling you, he isn’t

human. Not like us, anyway. He doesn’t blink. And the look in his eyes, it’s like he’s just

waiting for you to say the wrong thing so he can rip you apart. Freaked me out, I don’t mind telling you.”

“Yes, well, I don’t

doubt that he ‘freaked you out,’ Tom, but I’ve been watching him as often as I

could these last few days, and he’s definitely human. For one thing, the drums are starting to get

to him.”

Ed and Bowie looked at

each other in shock. One of the great

unspoken rules in the plant was that you did not mention the drums. You might think about them constantly, you

might want to claw your own ears out just to make the noise stop, but you

didn’t talk about them. Ed couldn’t

remember ever hearing anyone talk about them.

“As I said, I’ve been

watching him as often as I could, and when he’s in front of us he’s all

business, ruthlessly efficient and as charming as a snake. But when he thinks no one is watching, he

can’t do anything except stand there and listen to them. He just stands completely still, with his

head cocked to one side, like he’s frozen.

Yesterday he actually put his hands over his ears for a full minute

before he moved. You should have seen

it: his assistants didn’t know what to do.

Some of them have started wearing ear plugs to get away from the noise,

but obviously the Inspector couldn’t afford to do that.” Bowie finished the rest of his beer in a

single gulp and signaled the barkeep for another.

“So, since you brought

them up and all, what do you think –” Parker stopped talking as three more

beers were delivered to their table, “—what do you think the drums mean? I mean, where do they come from? I know we’re not supposed to talk about them,

but I’ve just always wondered about them.”

Ed wasn’t entirely

comfortable talking about the drums, but he had heard a few things, so he

answered. “The natives use the drums in

their religious ceremonies. Each drum

represents a different god, and the different rhythms are all prayers for

different things. So a fast, high drum

might be a prayer for rain, or a low, slow drum might be a prayer for…well, for

something else, anyway.” Ed stopped

talking for a moment. “Of course, that

doesn’t explain why they pound on the damn things all the goddamned time. I mean, who prays all the time? I guess I don’t know what the drums mean

after all, Tom.”

Both men looked at

Skinner Bowie, who was contemplating his fourth or fifth empty mug of the

night. Ed asked the question. “Say, Bowie, what do you know about the

drums?” Ed expected Bowie to know all

about the drums, but he was surprised by the man’s answer.

“I can’t say I know

much about them, except that I’d gladly welcome instant and total deafness at

the moment. What I do know, I learned

from Alexander Sloboda.”

“Old Man Sloboda? Why would he know anything about them?”

“Because, my friends,

he has not only entered the forest that surrounds us, he is one of roughly four

humans in the universe who has actually seen the natives.”

After ordering and

draining another beer, Skinner began to speak.

“About two weeks after

the drums started, I was stationed over on Sorting Three with Sloboda. I had never met him, and at first he ignored

my efforts to start a conversation. He

seemed nervous, but we were all on edge back then. I don’t think anyone had learned to block out

the drums yet, but they seemed to affect Sloboda more than most of us. No matter what I tried, though, the old man

wouldn’t talk. He just stood at the

line, doing his work and ignoring me.

“This went on for

three days, me talking, him ignoring me, while we spent eight hours a day

standing next to each other, until finally toward the end of the day he turned

to me and said, ‘I’ve seen them, you know.’

Well, needless to say, I wasn’t sure what he was talking about, and I

was so shocked that he was talking that I didn’t know what to say.

“After looking around

to make sure no one else was near, he told me a story that I’m still not sure I

believe. It took most of the night –

from the line we went back here, then to his bunk, and he never stopped

talking. He claimed that he was one of

the original site inspectors who first checked out this planet for the Company,

twenty years ago. Which obviously seems

impossible, except that he was so sincere it was hard to doubt him. The man was jumpy as hell, though; the drums

definitely had him spooked.

“He told a long,

rambling tale about landing right here, in the clearing this plant occupies,

and establishing a base camp. True to

Company form, the site engineers had to come down to the surface to do weeks of

work that would take a day if the Company would pay for the rights to a couple

of AI-level computers. Sloboda said they

spent the first few days making routine observations and taking copious notes.

“Then the drums

started.

“He said they were

just as loud then as they are now, and even more frightening because they were

so unexpected. You see, every scan and

reconnaissance mission had indicated that there were no indigenous populations

on the planet. After a lot of hemming

and hawing, they decided to send out some people to investigate. Sloboda was one of them.

“I won’t bore you with

all the details of the journey into the jungle that he shared with me: detailed

descriptions of practically every plant and small animal they encountered, as

well as a truly encyclopedic list of minor injuries and aches he accrued during

the three days they traveled inland.

Suffice it to say that it’s a very hot, lush, humid jungle, with lots of

thick brush, tall trees, little light, and no easy paths.

“After a week of

traveling they encountered the natives.

This is where Sloboda’s tale broke down: he would not or could not

describe the natives or what he saw during that time, and several times he

started to break down and cry. I do know

that several men were lost immediately before contact. Sloboda swears he saw several thousand

natives in a vast clearing in the middle of the forest, and every last one of

them was pounding on a drum, everything from tiny hand-held skins up to oval

drums standing ten meters tall, but that was all the detail he could give

me. His tale became less and less

coherent, until he seemed enraged and terrified at the same time.

“Finally, after

talking for hours, Sloboda suddenly stopped and stared at the wall silently for

a while with a look of terror on his face.

After ten minutes of this, during which time I barely moved for fear of

sending him over the edge, he turned to me and, in absolute terror, whispered,

‘they want another one.’ Just a

whispered question, but it sent chills up and down my entire body and gave me

nightmares for a week afterward. I got

out of there pretty quickly after that and haven’t spoken with him since.”

Ed and Tom sat

silently for a while after Skinner finished speaking, nursing their beers and

thinking about Old Man Sloboda’s story.

Ed wasn’t sure what to believe and what to discount as the ravings of a

mentally ill mind. For one thing...

“If he was a site

engineer, why would he be working on the line as a common laborer twenty years

later?” Ed had a feeling the answer was

obvious, but he couldn’t work it out.

Skinner answered quickly, but in a way that made Ed at least feel like

the question hadn’t been a stupid one.

“I’ve wondered about

that myself, Ed. The only thing I can

figure is that Sloboda saw something the Company doesn’t want advertised. They didn’t want to kill him, but they also

couldn’t let him off the planet, for whatever reason, so they stuck him in the

plant, where he couldn’t do any harm. A

sort of permanent exile, if you will.”

Ed thought about it

for a while. It didn’t feel right, but

he couldn’t come up with anything better, so he let it go. “Here’s another one: if the Company has made contact with the

natives, twenty years ago, why haven’t they ever announced that? If they’ve never made contact, as they claim,

why is simply entering the woods a crime?

For that matter, the Company claims that there are no natives, and the

drums are actually just a natural phenomenon.

I saw it on the All-Net before I came here. Why the big denial? What are they hiding?” Ed fell silent, a little surprised at

himself. Skinner sat quietly, evidently

in thought, while Tom looked more than a little confused.

“Those are all good

questions, Ed, and I don’t know the answers to any of them. Here’s one more I can’t answer, and it was

one of the last coherent things Sloboda said before he scared the hell out of

me: why did the drums stop after the

last inspection ten years ago, only to start up again a few months before the

next scheduled inspection?” With that,

Skinner stood up and excused himself before wandering toward the exit. Tom sat a few minutes longer, still looking

confused, before he too got up and moved toward the exit. Ed stayed until closing, chewing over

questions with no answers and wondering where this was all leading.

The three men didn’t

talk much over the next few days about Sloboda’s story, but Ed thought about

the story constantly, and especially pondered the connection that Sloboda had

implied between the inspections and the drums.

No matter how much he chewed on the problem, though, he couldn’t make

any sense of it. It was like a Gordian

knot, impenetrable and ultimately, he suspected, unanswerable. Perhaps there was no connection, and the

drums’ stopping after inspections was sheer coincidence. The more he thought about it, the less sure

he felt about anything, including the likelihood that the old man’s story was

true.

The one thing Ed was

sure of during that time was that the drums were finally getting to the

Inspector. Skinner had said as much, of

course, but not it was obvious to everybody in the plant. The Inspector still wandered the plant at all

hours of the day, observing and whispering notes into his wrist, but he was a

changed man. His pristine white suit

glistened no longer; it was smudged and smeared with grease and smoke. He didn’t seem to notice. His short hair was dirty and unkempt, and he

ran his free hand through it continuously.

Where before he had glided from station to station, he now darted about

uncertainly, practically running from spot to spot before stopping altogether

and standing silently, head cocked, for minutes at a time.

The Inspector

approached Ed once during this time. Ed

was shocked by the man’s appearance: up close, his eyes were blood shot and red-rimmed

and blonde stubble stood out in uneven patches on his cheeks. His lips were cracked and bleeding and he

mumbled constantly under his breath. As

he stood staring at nothing, Ed thought he heard the phrase ‘drums of Hell,’

but he wasn’t sure. After staring into

space for five minutes, the Inspector turned suddenly, glared at Ed, then

turned and sprinted down the narrow gangway, up a flight of stairs, and around

a corner toward Borla’s office. Ed

shrugged and tried to look nonchalant as he returned to work, even though his

heart was pounding after the strange encounter.

Three days later, Ed

found himself back in the bar, sitting with Tom and Bowie and group of other

men around the table. As before, the

place was overflowing with exhausted men who were, for the most part, drinking

quietly and trying to ignore the pounding drums. When a mine rat burst through the doors at

the far end with a crash and a yell, Ed started awake. Everyone turned to stare in shock at the man

who was now trying to talk and catch his breath.

“He’s…gone…forest…he….” Finally the man stopped trying to talk and

stood for a minute, breathing deeply, while everyone, Ed included, got up and

surrounded him. Skinner somehow worked

his way to the front of the crowd and handed the man a mug filled with dark beer.

“Here now, drink this,

son, and take your time.” Skinner looked

around at the curious, shocked, or angry faces surrounding him. “Don’t take too much time, though, huh? Now, what is it? Nice and easy, there you go.” The man had recovered enough to speak almost

normally.

“The Inspector. He’s gone.

He –” The man was interrupted as a hundred men starting shouting

questions at once. Skinner held up his

hand for silence, and then motioned to the man to continue. Perhaps realizing that he wasn’t doing a very

good job, the man took a deep breath and started again.

“The Inspector is

gone. He walked into the forest alone,

about thirty minutes ago. Just walked

out the back gates and into the trees by himself, carrying nothing but a

flashlight. I happened to be coming up

from my shift and saw him walk by, with Borla and the rest close behind, so I

sort of followed along. Borla and

everyone else stopped about twenty feet out of the gate, but the Inspector just

kept on going, walking fast and straight, like he knew just where he was

going. I was so shocked I just stood

there. Borla must have been shocked too,

because when he turned around and saw me he didn’t do anything, just said, ‘He

says he’s going to stop the drums’ and then turned around and walked back into

the building.”

All bedlam broke loose

now, as everyone started talking, laughing, and drinking at once. A dark man in badly stained coveralls jumped

up on the bar and motioned for quiet.

“To the

Inspector. I don’t know if he’s the

bravest man here or the craziest, and I don’t really care as long as I don’t

have to look at him anymore!” This was

met with raucous laughter and enthusiastic drinking. More toasts followed, all centered on the

basic theme that the men didn’t really care what happened as long they didn’t

have to deal with the Inspector any longer.

The party grew so loud

that it nearly drowned out the drums. Ed

realized with amusement that he couldn’t even really hear them properly anymore

over the shouting and laughter. Even when

he stopped and really tried to listen, they weren’t there…there was no pressure

in his chest….

“Ed, what’s

wrong?” Skinner looked mildly

concerned. Ed put his fingers to his

lips and focused on trying to detect the drums.

Nothing. He looked at Skinner in

something like disbelief, a lump forming in his throat at the mere

thought. He couldn’t do more than

whisper to Skinner.

“The drums. Listen.”

Skinner looked at him skeptically, then shrugged and listened. His expression moved quickly from quizzical

interest to doubt, then to something approaching awe.

“Quiet!” Skinner’s voice roared over the din,

instantly getting everyone’s attention.

There were a few protestations, but within a few seconds almost complete

silence had descended.

Silence without

drums. They had been a part of the

fabric of life for so long that it took some men a while to realize what was

missing. Men look at each other in

wonder, in awe, even in fear and then, as the deafening silence stretched from

twenty seconds to thirty, from thirty seconds to a minute and then two, a look

of absolute joy spread over the face of everyone in the room. Grown men, some of the toughest Ed had ever

known, stood and wept openly but quietly, listening to the indescribable

silence. Later that night there would be

loud and joyous parties, but for now, all over the plant, men simply stood

silently and thanked whatever gods they prayed to that the ordeal with the

drums was over. The message spread

quickly throughout the plant that management had declared a general holiday.

For Ed, as for many

other people, the absence of noise was overwhelming; he felt almost lost

without it at first. But only for a

short while; much, much later that night, when he finally crawled into his

bunk, delirious and overwhelmed, he slept peacefully for the first time in

months.

Meanwhile, as Ed and

his friends celebrated the end of the drums and the inspection, Plant Inspector

Borla sat alone in his private office, high atop the northernmost tower of the

complex, and composed a message to be sent to the Company’s President. The President was a man who valued brevity

and concision above all else; the composition of the message was a tricky

business. In the end, Borla settled on

the following:

Mr. President:

Inspector’s visit a

complete success; nervous condition manifested exactly as predicted. Sacrifice seems to have been satisfactory to

natives; operations should continue unimpeded for another ten years. I shall contact you at that time to arrange

for another inspection.

Yours,

Plant

Manager Borla

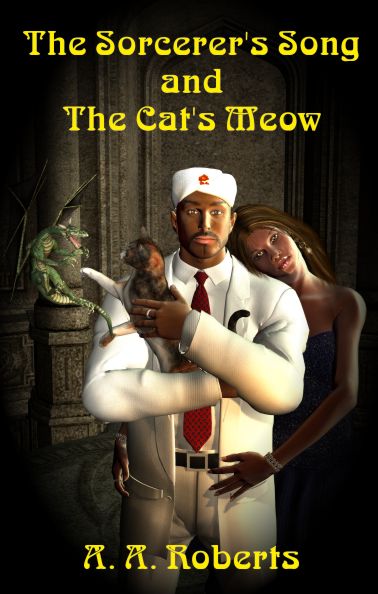

A cat and her sorcerer, a beautiful dream weaver, an evil voodoo priest,

a bunch of man-sized rats, an army of really big bugs, a crazed randy rabbit,

some dwarves, dragons and angry three-toed sloths, New York City, the woods of Maine,

the sands of Arabia and the mythic lands of Avalon all come together for the wildest

most epic adventure you’ve ever read!!!!

A cat and her sorcerer, a beautiful dream weaver, an evil voodoo priest,

a bunch of man-sized rats, an army of really big bugs, a crazed randy rabbit,

some dwarves, dragons and angry three-toed sloths, New York City, the woods of Maine,

the sands of Arabia and the mythic lands of Avalon all come together for the wildest

most epic adventure you’ve ever read!!!! The Sorcerer's Song and The Cat's Meow is an author's triumph and a reader's delight... What a wonderful, free-falling storytelling ride to get to the end of a fantasy that's about as close to purrfect as you can get.

M. Wayne Cunningham - ForeWord CLARION Reviews

A well-plotted story with vivid and riveting description of characters and settings, as well as an intense page turning battle, the book is a delight to read.

Tracy Roberts - Write Field Services