Please Help Support CTTA By Checking Out Our Sponsers Products

CTTA has officially

gone green with this story.

How to Dispose of Sneakers

by

Sue Lange

I slapped my wrist and answered: “Yeah?”

“We need you,” Buddy answered. “Where are

you?”

“At home. Where are you?”

I was surprised at the answer. North Beach.

Since the Coast Guard was the heaviest armed, highest funded, and most

technically savvy branch of the Militia, nobody fucked with the oceans. Most

you could expect to find at the beach was somebody pissing in the water. The

place remained pristine. Virginal even, until today apparently.

“There’s white crap on

the white caps,” Buddy said on the buzzer.

“I’ll be right there,”

I answered.

Kissing my true love on her lips, I headed

out the door, board in hand and True Love’s sneakers hanging around my neck.

Shelly had requested I dump them for her because the Directory had no

instructions on how to recycle them. I intended on disposing them on the first

high school’s overhead wire I passed.

*

* * *

If the substance

lapping up on North Beach’s shore had any weight to it, it would have been

coating the sea floor and clogging the channels. As it was, however, there was

nothing to the stuff. It was light as air, floating on the top of the water and

giving everybody the creeps. They started referring to it as the “White Death.”

It spread out for a half a mile in all directions like the sheet of a giant

ghost fluttering down to the waters.

The cleanup crew

wearing blue neoprene dishwashing gloves stood back waiting for a full analysis

before jumping in. They were scared. Lab Services was down in full body suit

trying to scoop up samples, but the stuff kept floating out the top of their

samplers. They finally sent a gopher over to Pathmark to get a colander. They’d

never seen any illegals float before.

“What do you think it

is?” Buddy asked, huffing up the side of the dune where I stood watching the activity.

Buddy’s a cool kid. She’s kind of short in the knee and not the neatest of

dressers – always got a knotted tie or missing button or scratched lens – but

real sharp, otherwise.

“No idea,” I answered.

“Never seen anything like it.” I squinted to watch a cormorant trying to fish

in the depths beyond the floating layer. It finally gave up and flew off, a

line of the white scum clinging to its belly where the water line had been.

“That is disgusting,”

said Buddy.

“Yeah,” I agreed.

“Coast Guard here yet?”

“They’re setting up

blocks five miles out.”

“What about the

effluents?”

“Both clean, but the

tide’s coming in and we should be concerned about the estuary,”

“At least the Guard’ll

be too busy to annoy us there. Who’s working?”

“Noog. He’s just starting the

analysis.”

We headed over to the

purple aluminum sided trailer parked at the edge of the sand zone. I’d attached

my board to the front fender earlier, but hadn’t gone in yet to see what was on

the plate. The tiny stack up top emitting dyed exhaust from the inside fume

hood, indicated Noog was indeed cooking up a gumbo. Somewhere a scanner high

above the city was measuring and logging our emission, making sure we complied

with today’s limit based on air temp, wind speed, and overall ooziness of the

atmosphere. On a still day like today, Noog had to be very, very careful.

Inside we found Noog

papered, masked, booted, and breathing his own specially designed

nitrogen-oxygen mix, ester-enhanced at the tee with the flavor of the day. In

spite of the amenities, Noog looked uncomfortable in his containment tent at

the far end. The air conditioning just wasn’t keeping up.

He moved at intervals between his pH probe

and billion dollar chromatograph unit as if trying to decide which analyzer was

the best. Nothing seemed particularly suited to the white immiscible that clung

to both birds and water but not samplers. Just didn’t want to liquefy. The hood

alarm buzzed with every drop of acetone from his autopipet. Each time it went

off he had to stop the titration and wait for it to clear before continuing.

The tension was killing me. I asked Buddy

to hang with Noog to keep him from going bonkers while I stepped out for a

while.

“Just let me know when that box spits

something out: number, name, license, anything. I don’t care. Even just a

carbon percentage,” I said.

Then I set out to round up my usual waste

suspects—the little mom and pops that get busted every other year for

infractions of rules impossible to follow when you have little capital.

Gadge Tundy was the best of the shoe string

outfits. Like everybody else, she was located at the Hook a couple miles up the

coast from North Beach. Lying at the end of Ocean Boulevard and butting up

against the Soft Kills swamp, the Hook’s insanely low leases made it perfect

for businesses like Tundy’s that spent their efforts working around the

complicated legal system of waste disposal.

I turned down Ocean and rolled past

bungalows, plastic palms, and pastel colored sidewalks. After several miles,

the boulevard ended in a narrow lane surrounded by a conclave of cylindrical

incinerators, garbage heaps, compost buildings, holding pens, offload docks,

and low-slung front offices. The place was a mess of big trucks maneuvering in

and out, beeping back up signals, semaphore activity, and gangs of pile diggers

singing the tune of the day as they dug the waste out of the trucks and moved

it into nearby pits.

Still on my board, I squeezed in between

the rigs heating the air with recombined diesel exhaust. Every once in a while

the board rose a little on the mini thermals and I’d have to force it back down

by manually reducing altitude. I crept forward in this manner until I reached

the last shack on the left—the flat-topped, one story salmon-colored affair

with moldy bamboo Venetians at half mast. The number on the aluminum and Lucite

front door was 125. That’d make it 125 Marrow Lane–Gadge Tundy’s.

Tundy’s door clanked with a discarded gear

and bicycle chain set-up dangling from the door handle, an industrialized

version of the sleighbells-on-a-leather-strap that gift shops hang at

Christmastime to alert the keeper that a browser has entered the premises and a

sale might be forthcoming. The door panel had been scraped shiny from the

thousands of egresses and ingresses it had experienced since the day, ten

optimistic years ago, Tundy or her brother had rigged up the chain.

A pixie-haired woman of the squat variety

entered from the back, a scowl on her face. She tamped her forehead with an

oversized bandana—more towel than handkerchief—and ran it through her hair

before stuffing it into the back pocket of her overwhites. The thing trailed

onto the floor, creating an obvious dirt trap. I let it go.

“We don’t handle sneaks,” she said, turning

to head back to the firepit outside. Then suddenly she spun around and said,

“Skosh! I thought you were a customer. What’s the deal with the treads?” She

took a few steps towards me, broad smile across her cherubic face, pointing at

my chest.

I had forgotten about Shelly’s shoes

hanging around my neck so I was a bit confused at first. I looked to where she

was pointing and then back up to her.

“Ah, I’m just on my way to school to make a

transaction, but I needed a little help from you.”

“Sneaks are fairly easy, Skosh; can’t

believe you’re here about that.”

“I’m not actually. How about lunch? I’ll

buy.”

“This must be serious,” Tundy laughed. She

grabbed my elbow to steer me out of the building. The door clanked behind us.

We swung down a dirt path that ran

alongside her building and then around the pit in the back. She signed the

international eating gesture—rubbing the stomach in a circular motion and then

pointing to the mouth—to her brother, Morton, on the far side of the pit. His

face and clothing were smeared with gray slime from a morning spent stoking

garbage.

Past Tundy’s big storage shed the ocean opened before us, sparkling

clear and happily oblivious to the little floating white things a few miles

down south. The path widened as the various trails created by waste operators

joined it, leading to the Café.

The Café sits in the middle of the tidal

marsh at the edge of the Hook. The swamp serves as a natural boundary between

the waste pits and the next civilized neighborhood over that consisted of a few

stray houses of the low rent variety—lonely and perfect for misanthropes or

people with no impressive means of support. Once upon a time, I lived there.

We followed the path as it connected to

what someone might have called a wooden walking bridge, but then someone else

would have pointed out was nothing but a few boards hand tacked to a frame of

Thompsonized two by twelves. The wood was held up out of the muck by blobs of

concrete. Who made the bridge nobody knows. How the cement blobs and two by

twelves came to be there nobody knows. When the Café was built, nobody knows.

That it was even registered was doubtful. I inspected its operations once and

gave it a lifetime pass just so no lesser inspector would ever make the same

mistake of checking it out. The paper trail was nonexistent; apparently the

place had never been bought or sold. Nobody owned it. The building codes—fire,

waste, electrical, plumbing, integrity—were disregarded as if they didn’t

exist. If it rained or snowed outside, it rained or snowed inside. It had

neither heat nor air conditioning. Fly paper strips hung from the ceiling as a

nod to insect control. A fan graced the cook’s presence in the summer, but not

the customers’. The toilets were used for grease dumps and therefore hadn’t

worked in years and in fact probably led straight to the water below the

building. Cockroaches were everywhere including the soup. How could I let this

place remain in existence? I reasoned the folks in the Hook deserved to have

some place close for lunch. Besides, how much damage can a fire in the middle

of a swamp do? Or a complete collapse? Or an illegal dump of food waste? A

swamp’s the best solution for pollution in my opinion. And the food was out of

this world. You can’t imagine what a half-way talented cook with no

restrictions can do.

We walked over the tidal water and salt

grass to the middle of the swamp proper where the Café stood on stilts. On top

of the water surrounding the Café lay a familiar ooze—an accumulation of years

of dumped fryolator oil. Here and there a fish head bobbed up on its side. I

could see what the catch of the day was just by perusing the flotsam in the

landscape.

The window screen by our table held a

thousand years of dead bugs that had either valiantly fought for their way in

and lost, or valiantly fought their way out and lost. The table came complete

with a set up of salt, pepper, ketchup, Tabasco sauce, jerk chutney, and an

economy sized can of Raid. There were no menus.

We were the only ones in the house besides

a drunk in a Yankees cap at the end of the bar, chewing the ice in a long-ago

downed cocktail on the rocks. The bartender asked if we wanted anything.

“I’ll have a double burger and an iced tea.

Heavy on the ice.” I called over.

Tundy stared at me and then looked over to

the bartender.

“What,” I asked, following her gaze. “Oh,

yeah, I know. Ice is extra. No problem.”

“That’s not it,” Tundy answered. “The Café

is vegetarian now. Eggs and fish are about it for animal products.”

I stared at Tundy and then at the bartender,

hoping he’d remember me as the guy who passed the permanent inspection twelve

years earlier and for that special treatment he’d pull out a couple of frozen

patties left in the deep freeze from the days before they went meatless.

“Sorry,” was all the guy said. He was no

doubt not even born twelve years ago.

“What gives?” I asked Tundy.

“Everybody around here turned vegetarian,”

she said. “Nobody can stomach processed cow or pig anymore.”

“And chickens,” the bartender called over.

“We haven’t sold so much as a chitlin’ in three years. Folks just stopped

ordering meat, so we stopped getting it in. Fish or eggs from South America.

They’ll order that. We’re all bean curd and water cress now. How about a nice

boullabaise?

The question conjured up the floating bass

heads just outside the door. I answered: “How about a nice fried tofu

sandwich?”

“Fine.”

“And an…”

“Iced tea, heavy on the ice. You got it.”

He turned to Tundy with eyebrows raised.

“The usual,” she said.

He turned to put the order in to the kitchen

which was actually just a guy working the center grill behind him.

“What’s the deal,” I asked Tundy. “This a

fad, or what?”

“Listen, Skosh, when you deal

in waste like we do, you see a lot of stuff. We know what really goes into the

hot dogs, know what I mean?”

“No. I deal in waste, too. What are you

saying?”

“What I’m saying is, if the food industry

was regulated as much as the waste industry, I’d be downing a slab of ribs with

the hottest cognac Tabasco this side of the Mason-Dixon line, but as it is, a

hemp patty on rye with a slightly aged Jack Daniels’ ketchup is as good as it

gets.”

“Tundy.”

“What?”

“You’ve joined the ranks of the paranoid,”

I said.

“Skosh.”

“Yeah?”

“You’ve joined the ranks of the

unenlightened,” she said.

Lunch came. Hers smelled much peppier than

mine, and her face turned bright red with the first big bite. By the end of the

meal the sides of her face dripped tiny streams of sweat. She pulled the

bandana out regularly.

“Listen,” I said at one point, more to give

her some relief than because I needed to get back to business. “I’ve got a real

mess down at North Beach. What have you heard about any barge dumps recently?”

“Nada. Things are copacetic.” She scarfed a

chunk from the tubular wrap, barely catching all the red sauce. Her eyes welled

up. “Nothing,” she choked out and went for another bite.

I wasn’t that surprised at her answer.

Marine events just didn’t happen. I hadn’t seen a spill or illegal dump or so

much as the taking of an undersized bluefin in 25 years. The Atlantic was

healthy, alive, and clear.

“So who dumped?” I asked.

“Look, Skosh. You don’t get it. Nobody

dumped. If they had, we’d all a heard about it or seen it even. We don’t know

nothing about a load of sludge respiring aerobically up on the beaches of Gotham.”

“I’m not talking about some illegal weekend

toilet barge flush.”

“So what are you bugging me for?”

“I’m interested in the little white spheres

with a practically zero specific gravity. Non-polar; spreads out like oil. Totally

immiscible, and thus far unidentified. It clings to birds when they fly out of

it. What is it?”

“What kind of white?”

“I don’t know. White.”

“Off-white, dirty-white, clouds white, snow

white, foaming-at-the-mouth white, cream, eggshell, or bleach?”

“White white. What is it?”

“Spreads on the surface, eh?”

“What is it?”

“You need a CDC from the Twentieth Century,

my guess. And you need to stop looking for a point source, my second guess. And

there’s no way to get rid of it, my third guess.”

“What is it?”

“Don’t know. Never worked with floating

spherical white stuff that gets stuck on birds. Probably something

petrochemical that hasn’t been manufactured for centuries. I imagine an old

cask full of sin cracked somewhere upstream and now this stuff that doesn’t

ever break down in my grandkids’ grandkids’ lifetimes leaked out. Plate

tectonics, man—beautiful thing. Gives us diamonds, minerals, mountains, rich

soil, and last millennium’s crap. Don’t bug us little guys on this one, Skosh.

Nobody dumped. It’s non-point source all the way. Non-point source. Look it up

in the old manuals.”

“Look what up?”

“You don’t get it, do you?”

“Get what? You haven’t told me anything.”

“Look, I don’t have the reference links. Go

down to the archives, the ones not digitally rendered, and find an old chemical

registry. Look up hydrocarbons. Under P. For Polystir. The stuff is ancient.

I’d love to help you, but I got some vacuuming to do.”

She stuffed the last bit of lunch into her

mouth and stood up. Separating her mealware into the various components, she

dumped each into a different receptacle at the far wall. I noticed the paper

napkins wound up in the plasticware and the tray found it’s way into the

burnable bin, but I was too dumbfounded from her reaction to reprimand her.

Here’s a woman without batting an eyelash,

can eat a sandwich capable of corroding battery housing. I mention little white

things crapping up the sand and next thing I know she’s on about the state of

her household. She knows something. You think?

Tundy returned to the table and gave me

peck on the cheek. “Gotta run, Skosh. Really good to see you,” she said. I

watched her scurry down the floating plank and up the path back to her

operation.

Leaving a twenty on the table, I walked out

the door, grabbed my board, and followed her at a distance. She ran all the way

back. When she got to where Morton was still shoveling and directing the jib

over a pile of construction debris, she waved frantically to get his attention.

He signaled to the operator to cut the crane and Tundy ran over to him without

waiting for the proper amount of time

following shutdown of an overhead machine to enter the ten foot safety zone

without a helmet. Safety infractions fall under my jurisdiction, but again I

stifled the urge to issue a ticket.

The two conversed a moment and then headed

over to the office. The crane operator waited patiently for instruction. After

two hours he jumped down from his booth and headed home. I know he waited two

hours because I was watching the whole time. Tundy and Morton remained in the

office, oblivious to the fact that they were paying an idle man.

I had a feeling I should be consulting my

pocket dictionary while I waited, but I suspected the term “Polystir” would not

be in there so I didn’t bother. I considered blustering into Tundy’s office

while they were still sniffing around the database, but it went on for so long,

I assumed they were having difficulty scaring up the info. She herself had said

it wouldn’t even be digitized.

So I left. I was well on my way to figuring

it out by then anyway. Non-point source she had said. Didn’t make sense because

she had also said it was probably a leaking cask. Which was it Tundy? Leaking

land fill or run off? She was hedging her bets: throwing me off but helping me

at the same time. If I never found the culprit, she’d have the goods; if I did,

she could claim that she helped me. I loved Tundy. Smart cookie, but not smart

enough.

Returning to the beach I found the cleanup

crew had left for the day. Most of the mess was still there. A cop stayed

behind to patrol the rope and keep potential night swimmers from inadvertently

fouling themselves in the unknown scum.

I called Shelly to let her know it would be

one of my late days.

“Did you get rid of my shoes?” she asked.

“Uh, no chance yet. I’ve just been to the

beach and the Hook. I’ll take care of it, though. Don’t worry.” I assured her.

I entered the lab trailer and watched Noog

doff his papers. He was drenched and appeared to have lost a couple of pounds

during the day. The knees and elbows of his normally skin tight body wrap hung

off him like his big brother’s jammies. Exhausted, he sat in front of the

office fan, drinking in air like water, burping it back out at intervals. Bits

of his hair were plastered against his face which was so red he looked like

he’d just been thrust from the fetal sac.

“You okay?” I said sitting down opposite

him.

He rolled his face in my direction, the

weight of his head making the motion, as if moving his eyes was too much of a

strain. He said nothing.

“Where’s Buddy?” I asked.

He closed his eyes slowly and then opened

them again. It was actually a blink in slo-mo. “I told her to take off; I can

call it in.”

“Do we have an answer yet?” I asked.

He inhaled deeply and nodded toward the calculator

humming at the edge of his analyzer space. “The computer’s taking a long time.

It’s too hot in here, and the database connection is…far away.”

He said it like he was the one that was far

away, then he yawned and added, “Wake me when you hear a beeping…”

”Before he could finish the “from the

analyzer,” his mouth dropped into the fly-catching position.

I sat for half an hour or so, got antsy,

and taped a note over the analyzer readout: “Call me when you know something.”

Then I took off.

From the beach area I walked over to where

the river emptied into the Atlantic. The mouth of the Huddie River had jetties

on either side of it, extending beyond the swimmable area of the beach. A few

yards upriver, the near jetty evolved into a corrugated sea wall about waste

high enclosing the high tides and keeping the townies from falling in. A “No

Wake” sign was attached to a buoy anchored in the middle of the river, which at

this point was about 100 yards across. The sign bobbed up and down as passing

day boats flouted its directive.

I considered walking upstream for a while,

past the high rent houses with porches on the second floor. The wall went on

for several miles from there past the downtown area with its over priced

eateries, none of which could compare to the Café in price, excellence of food,

or sheer ambiance. In the end I decided not to head up that way since I knew

I’d get nowhere following the river. The sun was waning. Even now I strained to

see any little white floaters. In an hour it would be useless. Besides, nothing

was clinging to the sides of the sea wall or the buoy in the middle. It didn’t

seem likely that a steady stream of white bubbles was floating down river from

a non-point source. I suspected that for the first time in my relationship with

Tundy, she didn’t know what she was talking about.

That would be strange indeed, so I called

her.

“Just wanted to let

you know, “ I said. “We’re still working on that Polystir ID, however, we do

know that it’s totally non-toxic. We’re going to go ahead and clean it up

tomorrow while we’re still checking out the particulars. You interested in the

contract?”

“I’m always interested in

work,” Tundy said.

Lab says the stuff is

non-destructable so it’ll be a seal and save op. You won’t have to recycle it,

and in fact you won’t even be able to return it to your pit. Has to go straight

into a cask and back to the mound. Could be a good payout for you once all the

paperwork comes back. I’ll give you a shout around noon if you’re interested.”

For half a moment she

didn’t answer. Then: “To be honest, if the stuff is doing what you’re saying

it’s doing, it’s not going to weigh much. I doubt if it’s worth it for us. We

get paid by the kilo. Whyn’t you contract a smaller outfit, somebody down the

line? Or maybe wait and see if it drifts out. As long as it’s non-toxic what’s

the diff?”

“It’s my job for one

thing, but I can see your point. Thanks for your help, pal, I’ll catch up with

you on the next one, the sludge at the bottom of the pond one. It’ll be so

heavy you’ll need a new crane just to haul it out. How’ll that be?”

“Buried treasure,

Skosh. That’s what I’m looking for.”

We rang off, both of

us satisfied the other was totally fooled.

I walked back to the

beach and relieved the cop on duty. The sun was setting so I called Shelly to

let her know the obvious: instead of merely working late, I’d be out all night.

“Did you dump the

shoes?” she asked.

“Damn, I forgot I

still had them,” I answered, lifting the left one up to eye level.

“Just bring them home.

I’ll take care of it. I’ll ask Monica what she did with hers. She had a

disposal last year.”

“Shelly, this is my

bag. I can do it.”

“I’m just saying you

seem really busy. It’s no bother, really.”

“Of course it’s a

bother. If it wasn’t a bother you wouldn’t have asked me in the first place.”

“Fine.”

*

* * *

Just as I had hoped,

midnight produced two shadows—one fairly short—hovering up the beach in

semi-darkness. They carried no hand held lights to show the way, but the moon

provided ample illumination. I watched from between two clumps of dune grass

about 100 feet up the beach and off to the jetty side. Once they began their

work in earnest I crept to the edge of the roped off area to get a better look.

The day’s wave action

had pushed the white plastic beads into concentrated furrows on the shoreline.

They looked like fat rolls on the neck of an obese person. The two shadows

unfurled a net along the shoreline where the beads lay. They worked quickly and

silently, the only sound being a wave here or there cresting lazily on the

beach. The shadows moved to pull on the net when suddenly a call came in on my

talker, it’s buzz breaking the sacred silence of the night like an

inappropriate cough in church. The shadows abruptly stood straight up. I

fumbled with my unit, clicking it down to silent. Unfortunately the unit’s

incoming light continued to flash, exposing my position before I could pull my

sleeve down over it. The shadows fled. I did not give chase. I’d see Tundy

tomorrow.

“Yeah,” I answered my

wrist.

“We know what it is,”

Noog, wide awake and triumphant, answered.

“Yeah, and…” I said.

“Syrofoam,” Noog

answered.

“Oh, yeah. That makes

sense. Now I get it.” I headed towards the trailer. “What the hell is

Styrofoam?”

“Hydrocarbon compound

invented in the 1800s. It’s made by injecting pentane gas during the

polymerization of styrene. Results in an indestructible, lighter than air

compound: a non-interactive, non-toxic, non-flammable, non-corrosive substance

used for everything from house frames to packing filler to Teddy Bear stuffing.

Great insulation and cheap as tree leaves. Banned 2053 when the plastic zero

tolerance law went into effect. The stuff has no half-life: it never breaks

down. Unrecyclable and totally illegal now. Some old building must have

collapsed up state.”

“Noog,” I said,

opening the door to the trailer and clicking my phone off.

He looked up. “Yeah?”

“You’re incredible. Go

to bed.”

“I just got up.”

“Go home then.”

“This is my home. I

live here.”

“In a beach house?”

“No, here.” He pointed

at the floor of the trailer.

I stepped back and

closed the door, locking it first. Noog was definitely a nut job. But he had a

knack for finding cheap digs.

I returned home on my

board pondering Styrofoam, the night air slowly chilling me. I completely

forgot Shelly’s shoes still hanging around my neck until I walked in the front

door. She was asleep already so I sacked out on the couch in the front room,

hoping to wake up early to avoid getting teased.

Didn’t happen. I woke up to Shelly tugging

on the shoes. She was trying to ease them up and away without disturbing me.

When she saw I was

awake, she said. “I’ll do it.”

“No, no I’ll do it.” I

sat up and made a grab for the shoes. “There’s no need for you to make a

special trip. Besides, you don’t know where to go.”

“You could tell me,”

she said pulling the shoes out of my reach.

“I’m going out anyway.

I’ll do it!” I snatched the sneakers back out of her hands.

We argued back and

forth a little more, poured ourselves some breakfast, and then I departed in

peace for Tundy’s.

I entered through the

clanking door of 125 Marrow Lane and, without waiting for acknowledgement,

pulled up a chair. “Tundy,” I said.

Morgan and she sat

listlessly drumming their fingers on the desk, tall lattes perched in front of

them. Neither appeared anxious to get to the mounting pile of debris in the

backyard. It was a dull morning, lacking the usual energy a day of lucrative

waste contracts brings. They grunted simultaneously when I sat down, but

neither looked up.

“You gotta tell me, “

I said. “What is it about Styrofoam?

They both started.

“Oh, and a…” I said,

sitting back in my chair. “I rolled up your net. It’s in the lifeguard’s shack

if you still want it.”

“Hm.” Tundy croaked,

like she hadn’t been drinking anything and her throat was parched.

“Look, I don’t care if

you steal government waste, but why is it so valuable to you?”

She shrugged a little

and closed her eyes in a “Who knows?” kind of way.

“Total immunity,” I continued.

“C’mon, I’m not going to hang my best gal.”

Tundy cleared her

throat. “Skosh,” she said and then stopped to take a swig of the latte. She

swallowed and then inhaled ceremoniously. As she let her breath out, her

shoulders drooped from the effort. “This is way over your head. Just drop it.

Forget about it.” As an afterthought she added, “And I’m still not handling

your sneakers.”

“Forget the damn

sneakers,” I raised my voice a little. “Why is this way over my head? Is it

some conspiracy or something?”

“Conspiracy? There’s

no conspiracy. Just a commodity clogging up the breakers, keeping the people

from their god given right to bathe risk-free. I’m just doing my duty as usual

and you step in.”

“I told you you could

have the contract?”

“I don’t want the

contract, I want the stuff.”

“Why? This a museum

gig? Just tell me, I’ll help you out. But first I gotta know where it came

from. Polystir, my ass. I can’t be having this secretive bullshit with no paper

trail. You know this.” I sat forward, looking her right in the eyes

“Relax. No, it’s not a

museum gig; this is not tourist type material. I don’t know where it comes

from. I just been hearing things about it all my life. I’ve never seen any

before, never dealt with it. But I study maps and old manifests, plan trips out

to the desert to the old landfills, got my pans and scales all ready to go. But

every year something comes up – a stiffer fine; a new regulation requiring a

bigger, hotter, yellower flame; the silo busts a peg; or Morton gets some weird

disease only waste handlers get and I have to call in a specialist. I never

seem to be able to put the cash by and get me a ticket to the periphery.

“But I always keep it

in the back of my mind, and then yesterday you come in here with this story about

little white plastic baubles floating on the beach. I don’t look no gift horse

in the mouth, so immediately I make plans to bottle the stuff and off load it

first chance I get. I go out there to collect and get chased off by some odious

goon on the beach, but I figure I’ll find a workaround. So I start making

calls. And whaddya know? First time ever, nobody’s interested in what I got

that’s valuable. It’s like it’s hot. Nobody’s biting, and nobody’s claiming it.

Nobody’s saying “nut.” Skoshy, take my advice and forget this stuff. It’ll

float away.”

I watched her getting

animated. It was like all those thoughts had been rolling around in her head

since about two in the morning and this was the first chance she’d had to voice

them. She was frustrated. Morton was no help, getting sick like that and all.

I said nothing for a

while and then: “Can I see those maps?”

“Go ahead, ignore me,”

she answered, unmoving.

“I will.”

“Why?”

“I told you; it’s my job.”

She sat back and stared at me for a moment.

Finally she reached up lazily to open a desk drawer in front of her and extract

a crumpled map of the U.S. It looked like it had been hastily shoved into the

drawer, probably moments before my entrance.

I spread the map out on the desk, ironing

out the wrinkles with my hand. Various small and otherwise unremarkable areas

had been marked by X’s with a marker that had at one time been pink but was now

faded to tan. Labels with addresses traceable by Global Star had been placed

next to each X. Funny thing was, no X’s were located this side of the

Continental Divide.

I looked up at Tundy.

“Some sort of earth movement, a fissure maybe, and a crack in the surface of

the cask liner?”

She shrugged. “Possibly.”

“And

it got across the Mississippi over to here, how?”

Morton’s eyes watched

me. Tundy tilted her head, the way a self-aware smallish person does when they

know they’re in trouble and they can get out of it by being cute.

“Okay, so it is

non-point source.” I said after I could no longer stand Morton staring at me,

waiting for the answer.

“No question,” Tundy

replied.

“Where’s it coming

from?”

“Where’s non-point

source always come from?”

I spun and headed for

the door. Just as the chain there flickered slightly, as if anticipating the

pressure of my hand on the bar, Tundy called out. “Hope you like bean curd.”

For half a moment I

stopped and considered what that might mean, but then rushed out.

Hopping on my board, I

tried conjuring up a picture in my head of farm country. Who were my rural contacts

there? I dealt with the off-shore, municipal, and industrial waste of urban

decay. Never farm factories. I hadn’t been north of the city limits since back

in the day the city had limits. Now the megalopolis protruded way beyond the

edge of humanity’s close quarters and in fact somebody recently discovered

there is no edge. No neighborhood or district lines. Flat tax, square township,

population centers ebbing and flowing in every corner of the land. Nobody knows

their neighbors simply because of the sheer numbers of them. What’s more

everybody’s related through the double miracles of collective unconscious and

quantum mechanics. You just can’t get away. The country where “anything could

happen but nothing ever does?” On the contrary; it’s been happening there for

years. There and everywhere else. It’s cow condos and hydroponic wheat sheds

from New Amsterdam to Syracuse bustling with humanity: farm workers, lawyers,

front office stooges, haulers, maulers, pickers, packers, truckers, agents,

experts, ag opinionistos, processors, managers, accountants, cooks, bottle

washers, crumb cleaners, inspectors, and let’s not forget the prostitutes that

hang around all day. Might as well be Midtown.

But it wasn’t my beat, and I didn’t know a

soul.

I rang Buddy, told her about the Styrofoam.

Then I ordered a low-tech sieve unit coupled with brown bag crew to go mop up

North Beach and tag the load in my name, dated today, extension: indefinite. I

needed the stuff there when I got back. With luck they’d toss it into the lock

up next to the biohazards and nobody’d rifle through it looking for a lost

weapon or something of value long forgotten by a neglectful detective. Of

course Syrofoam would be there a long time, and not just because it didn’t have

a half-life. Nobody would know what it was. Nobody’d touch it.

I quickly hovered home

to grab a bite and let Shelly know I was going upstate. She begged me to give

her back her old sneakers which were still hanging around my neck. I remained

adamant. Nobody was going to dump for my girl—including my girl—but me. She

reached for the shoes, but I pulled back and ran out the door, skipping lunch

and forgetting the sneakers as soon as I hit the street. I guess by then they

were actually a part of me and I’d have caught a cold without the warmth of

their frayed uppers and flapping knotted laces about my neck.

I raced through the

streets heading north without a clear plan. I knew it would be pointless to

rifle through manifests and licenses down at the records office. I hadn’t heard

of Styrofoam because no one had heard of it. They didn’t teach it in school. It

wasn’t on the list of includes or excludes. It did not exist so who would have

registered its use? I knew I needed to investigate the source of the non-point

source. But where is the source of non-point source?

I headed toward where

I thought the farm factories lay, flying past coffee shops and cafes, and

barely registering them, famished though I was. I puzzled over what I would do

when I actually got to “farm country.” How would I know when I was there?

Up on 215th Street, I found

myself across the street from a school. I could hear the squeaking sneakers in

the gymnasium, the walls echoey with rebounding basketballs and the “huhs” of

players as they hit the floor after a lay up, and then the Coach’s whistle as

he ordered the next boy forward in the drill.

A lonely overhead wire with attached

streetlight held the requisite mob of lost or stolen-on-a-tease sport shoes.

Spotting the hanging mess jogged my memory. Shelly’s shoes. But they’d have to

wait; I was on a mission. I stomped the board and turned down the lane that led

to the banks of the Huddie, a few miles up channel from North Beach. If I was

to find the non-point source distributing little white trifles, I needed to

head upstream from here.

Once I was within sight of the water, I

directed the board north, flew over the embankment, switched in midair to water

media, and landed with a tiny splash on the downswing. I stuck close to the

shore, assuming that’s where I’d find the small creeks entering the fray and

distributing the Styrofoam. I’d travel up along the east side and back down the

west side. How to know when I should call it quits and turn around I had no

idea. Hopefully I’d find something before Albany.

A few hours the

high-rise apartments along the way had permuted to somewhat shorter buildings,

unmarked and hinting at secret industry. Earlier numerous directional signs

along the banks had included mile markers, enticements for eateries up on the

cliffs, and depth warnings for the bigger boats. Now just a few township

boundary signs showed up every few miles. The traffic dwindled as well to one

or two dinghys anchored here and there for a cast.

I didn’t see anything

so much as a soap bubble in any of the effluent channels I passed, but now that

I was in the land of compost bins open to the air and other bits of what I

thought was farm activity, I started to search in earnest. Gulls and vultures

circling over squares of concrete blocks implied carcass processing operations.

The no smell laws passed decades ago ensured sanitized operation, but the birds

gave everything away. Strict standards for charcoal filtering air left every

place on earth—pig wallows included—smelling fresh and sweet to humans. Birds,

however, especially those that are specializers in offal, are infinitely more

sensitive to chemical stimulation. If you’re looking for prey of the dead

variety, follow the birds.

A mile or so beyond

Poughkeepsie, a freshly worked pile of dirt with half a dozen shovels, sticking

up like flags claiming territory for the white man, caught my eye. Somebody

here had recently had a problem with a summer storm. The river had overflowed.

Or something.

I maneuvered my board

up to the bank, anchoring it in a cove of brambles with a “stay” command, and

crawled up past the makeshift levee. I could see a patch of rubber tire tracks

of the kind made by big yellow front loader type equipment.

About twenty feet

beyond the dike an acre-sized dead bin complete with circling black carryon

eaters stood. This particular bin was wrapped in a black mesh tarp that

prevented the neighbors—or prying river travelers perhaps—from viewing the

appalling decay within. I felt compelled to take a peak. Walking along the

wall, I eventually found a tear big enough to spy through. Moving my head to

various angles, I scanned the pile of dead flesh crawling with maggots and

other composters. Mostly it contained cow parts: a hoof here, an ear there, a

snout with bloated purple tongue, a complete leg sticking out from the middle.

The pile was a graying mass of fur and entrails exploding with white foam. The

cow mess floated on a sea of Styrofoam beads.

My heart raced as I

backed up, hand over mouth as if blocking the stench of putrefying remains. Acatually

I was disgusted with the sight of the white stuff. I tripped over a recently

mounded hill of clay as I backed away.

“Hey you!” came a

shout from behind me. “Get away from there.”

I craned my neck

around as the voice slowly registered. About three hundred yards away a process

building hummed along. In front of that two men raced towards me, arms reaching

forward like parents saving a child from stepping over the lip of a bottomless

pit. The front man suddenly stopped and raised a dart gun to shooting stance.

My thoughts congealed

and I jumped up reaching my hands in the air.

“City Waste!” I

hollered, indicated the tattoo badge on my right forearm with my left hand.

“Recon!” I added to clear up any mistakes as to whether or not I was

trespassing.

A swift “crack!’

reported as a dart shot out towards me, stabbing Shelly’s left shoe and

draining itself of the dart’s contents into the one remaining toe that was

still intact. The action implied two things: either the guy was ornery and he

wanted to assert his position, or he was somebody that didn’t like gawkers.

Either way he was pretty good with a gun; the shoe with the dart dangled mid

chest, just over my heart.

They say waste

management is the second most dangerous arm of the law right behind forest management.

I do not waste time explaining the finer points of my jurisdiction when the

person I am speaking to doesn’t appear to enjoy subtle rapport. Especially when

I don’t carry a dart gun of my own. I took off before he could re-aim and ran

behind the cadaver bin. Keeping it between me and the dart man, I retraced my

steps over the levee and crashed through the brambles where I’d stashed my

board.

Ignoring the pain from thousands of tiny

thorns in my skin, I grabbed the board

and allowed momentum to roll me down the bank to the water’s edge. I

threw the board out over the water and called out the startup sequence without

waiting to get the thing horizontal. It raced off on edge until it righted

itself about a foot above the water line. I clung to the front side, lying

prone on top and bouncing up and down like a jetskier crossing the wake of a

passing speed boat.

Making it around the

first bend, I screamed as a sharp pain shot through my left calf. Seconds later

it went numb. I let go with one hand to reach down and retract the dart,

keeping my knee bent to stop as much circulation as possible. Five minutes

downstream I slowed the board to safety velocity while making a sharp 90 degree

turn inland. I sat up, tore off my shirt to make a tourniquet just above the

knee, tightening it until my thigh turned into a bulge. Still heading west, I

punched a request into the board’s locator for the closest clinic. The

coordinates popped up and I yelled a “Go.” I had barely enough time to regrab

the front of the board before it angled off on a trajectory of its own

choosing.

I ordered a belt for safety’s sake. We were

flying at 50 feet for what seemed like hours but in reality was a mere four

minutes, swerving up and around buildings and trucks and the occasional people

mover. I kept my eyes closed to avoid nausea and vertigo as we nosedived toward

what I assumed was a building with a big red cross on its roof visible to those

in helicopters and boards if they have their eyes open which I didn’t. The

board locked onto the building’s homing signal and the speed increased now that

it was confident of its direction. Its alarm kicked in at 25 feet, repeating

“Waste Cop! Waste Cop! Waste Cop!” at deafening levels. All on the ground for

ten square miles were now aware that a crap officer was either in hot pursuit

of a nefarious dumper or else fighting for his or her life and any minute would

be hurtling at an insanely high speed toward the building with the red cross on

the roof and everyone in the vicinity would be well advised to seek cover.

I opened my eyes just

as the board came to an abrupt stop testing the integrity of the safety belt

manufacturer’s quality control team. I prayed the team had not been drinking

the day this belt passed through on the assembly line. They hadn’t; the belt

released at just the precise moment and position to jettison me through the

receiving window into the lap of the inflated landing pillow, medical

receptionist standing by to extract insurance information from me before

sending me off to Waiting Room B for three hours until just after the patient

with the shotgun wound to the head received treatment.

To avoid the three

hour wait, the board changed it’s repeating wail to a drone voicing the

diagnosis I had punched into it just before we moved into ramming speed 4

minutes earlier: “Code 13; this patient’s body has been breached by a

manufactured botulitic organism. Please dial med-411 and enter the appropriate

code for information on the antidote. He has fourtee…thirteen minutes before

entire body paralysis is complete.” The message repeated with the change in

time reminding the on duty staff how heroic they would have to be if said

patient was to avoid a quadriplegial existence fourtee…thirteen minutes from

now.

“Step aside, doctor,

I’ll take this one.” I heard just before I left consciousness, hoping this

wasn’t one of those crime dramas where the hero is slipped a mickey and wakes

up bound and gagged on a conveyor belt headed for one of those huge circular

saws one finds in a tree processing factory.

When I did wake up, I

was not, in fact, on a conveyor belt. Instead I was in a room with twenty other

groggy, life-saved individuals being forced to sit up by a burly

ciggy-behind-the-ear-type. “You can’t go home until you evacuate,” she said,

grabbing me under my arms to heft me up like a rag doll whose head won’t stay

put.

“I can’t,” I whispered, having barely

enough energy to get it out.

“You can and you will,” she said. “Or

you’ll stay here forever.”

If I had any inclination to differ, she set

me straight; I would be peeing by dinnertime if she had to kill me to do it.

The sad part was that five minutes later, when I woke a bit more, I realized I

did actually have to pee, but I had no strength to get up and pay my sacred

respects. Knowing my state, Nurse handed me a plastic bottle shaped like a

curved funnel, indicating it’s function for one and only one thing.

I spent the next four

hours waiting for the sacred duty to happen. During that time Nurse and other

members of the staff repeated a story to me of how Doctor Chubb saved my life

within 45 seconds of total paralysis. And by the way, where did I get the

snazzy board? they all wondered.

Finally I did relax enough to let go of a

dribble. By then I was fully awake and had passed through a fit of tremors,

nausea, agitation, involuntary eye muscle movement, uncontrolled vocalizations,

and a deep desire to jack off.

After I peed, they let me ring up Shelly to

come get me. When she got there, she told me that the clinic where I was

interred was located a short distance from an old high school. She’d passed it

on the bus ride up.

“I’ll just drop the

sneakers off there on the way back downtown,” she said, spying them on a nearby

stand where the staff had left them.

“Not in a million

years,” I said, grabbing and then tenderly placing them around my neck. “Those

shoes saved my life. I’m going to have them bronzed.”

She rolled her eyes,

but didn’t argue. I related my adventures with the dart man to her on the bus

home, carrying my board under my arm. I don’t think she believed me. She

probably thought I’d developed some sort of fetish fantasy with her sneakers.

What she reckoned I was doing in a clinic where Dr. Chubb had saved me within

45 seconds of total paralysis, I have no idea. Doesn’t really matter anymore.

Once home I slept through the night and

called Buddy in the morning. I told her the whole story and had her order a

cease and desist on the farm that my boards’ locator log had stated was at 41° 46’ 32” subsection 1QZ, assuring her the

perpetrators would be caught red-handed and that would be all the proof she

needed for the order. I took the day off and promised to return on Monday fully

healed.

She gave no indication

of believing the part about the Styrofoam but I convinced her to go and speak

to Noog, check out the bag of shit tagged for me in the lockup, and then come

to her own conclusions. For my part I hadn’t really come to any. I mean I

discovered a pile of decaying cows lying around in a pool of a material no

longer produced and in fact illegal. Someone tried to kill me presumably for my

discovery. What conclusions could I draw? I planned to go and talk to Tundy

again on Monday. I’d never get the whole story from the farmers, but Tundy

would fill me in on details. I suspected she knew full well what was going on.

I mean, why did nobody in the waste processing business eat meat anymore? I had

all weekend to draw some of my own conclusions on that score.

Saturday early

afternoon, preparing to shave, I stood in the bathroom, my socks soaking up

water that had leaked from the shower onto the floor. I didn’t know someone was

at the door until I heard Shelly speaking out in the hallway. If only I had had

the presence of mind to not admit someone who had gotten my home address from

work. It was illegal for an employer to have that kind of information, so when

somebody calls and tells you they got your address from work, you know they’re

lying. Sure as I’m still alive and breathing, I know you can get anything you

want if you pay for it. So somebody had spent something to find out where I

lived. Why?

I could hear Shelly

mumbling out in the hallway as I was standing in my soaking socks, but I

couldn’t distinguish the words. Then:

“Honey,” very quietly from the other side of the door. I opened it to let her

in.

“There’s a strange little man from the

mayor’s office says he wants to speak to you about Styrofoam. He got your

address from work,” she said.

I very stupidly

assumed that this person was some sort of farmer’s advocate and going to

explain to me that my perpetrators were in fact engaged in some sort of secret

research that had full governmental approval but couldn’t be divulged to the

public until the results were in. And yes, they had had a problem with the cow

bedding storage unit for which they were totally sorry and would be using tax

payer’s money to clean it up, make it right, ensure that it never happened

again, and how much would it take to keep me quiet?

I was insulted before

I even left the bathroom. Hitting the cold tiles of the floor in the hall

didn’t help my humor. I stomped to the doorway two steps down. Not much space

to get really huffy, but I was ready to blow up into the man’s face and tell

him how out of line he was and it didn’t matter if I was going to be demoted

for acting against some fat government agency, and who did he think he was,

offering a bribe?

It’s not that I’m

against bribes. It’s just that I need more incentive than some agribusiness

trying to skim off a little more profit. Secret research? Probably the

development of a miracle substance to replace a regulated and costly but known

to be safe feedstock. Or maybe this miracle substance can replace ten unskilled

workers. There may be no more unions, but I’m always on the side of the

proletariat in major head discussions such as whether or not to take a bribe.

All that was going through my mind as I stomped the two steps to the doorway.

The little man stood

in the hallway in a crumpled suit with grease-stained pants three sizes too

long and a coat too hot for August. His hair was white and what little there

was of it was combed over the top of his head. He was half my height and

smiling, beckoning me to come and sit and relax in my own living room which was

actually just an annex off the hallway. Three steps to the couch was it. The

only way you could tell it was a different room was because it had carpeting

and the hallway didn’t.

He led me to the couch and sat me down.

If he noticed I was naked, he didn’t

acknowledge it. Shelly handed me her robe with the faded and limp flowers

decorating the front. We sat down as Shelly brought in coffee for the man. For

some odd reason after she handed him his coffee, she plopped her sneakers,

still tied together, onto my lap. I believe it was her non-verbal way of giving

me a dig, probably to offset my annoyance that she had let the strange and

little guy in. Ah, Shelly, Shelly. To have a spat with you once again.

“Strange and little” summed up the man. He

was of such a light constituency, when he sat down on our rat-hair seat, it

didn’t give out the usual squeak and complaint that chairs of such poor

construction and advanced age emit. He sat forward and adjusted his glasses on

his nose as if he needed to see us clearly. When Shelly plopped the sneakers

onto my lap, he actually reached over and turned the left one over, inspecting

the damage from the dart.

He took a sip of coffee and then looked up

to start a story. A ridiculous story. His story that is now my story.

“You see, Skosh,” he said as if it wasn’t

odd that he used my nickname. “Everything came to a head in the thirties.”

This was not news. The tales of the farm

crises, the food shortages, the nuisance lawsuits, the health hazards of the

twenties, offset by the miracle cancer cures of the thirties comprised the

stuff of every school child’s history studies. Shelly and I looked at each

other and nodded in agreement, wanting him to get to the point quickly so we

could then state our defense of having given at the office and he might as well

move on to the next neighbor.

“We

know that, yes, but in what way?” he said, smiling.

“Easy,” Shelly blurted, heading right for

the conclusion. “The environment was cleaned up of free radicals.”

“Ah,

those little free radicals,” he chuckled. “They are pesky aren’t they. They’re

so, so, how did we put it? Reactive. That’s it. They’re so reactive.”

Shelly and I nodded enthusiastically again,

waiting for the significance of a reactive free-radical.

“And we’re so receptive, aren’t we?”

We shrugged and agreed again: yeah we’re so

receptive.

“The farmers in short supply and the feed

lots contaminated. What would you do? With gene invention research so common,

wasn’t it inevitable that one genius scientist would stumble across an ancient

formula for the least reactive synthetic known to man? The substance may not

have been reactive but it was highly controlled, with no economical way

to manufacture it even if it was somehow made legal. And how could this genius

keep the secret with its powerful ability to cure man’s most dreaded disease?

Stopped because of mere man-made law and sad circumstance. You know

bureaucracy. It would take years to get the substance deregulated, years more

to develop it. Its research had to be done in secret and once its possibilities

proven viable, how could it then be put into practice without shouting out the

obvious disregard of the law during the research period? This genius scientist

would save mankind and end up hanging for it. Is that right? Of course not! The

miracle drug, the miracle cure, the miracle feedstuffs had to, and has to

still, remain totally secret.

Shelly and I said nothing. We did not nod.

We kept hoping he would launch into the part about saving our souls, but he

didn’t.

He correctly took our silence as an

indication of our confusion. He did say “feedstuffs” after all. The story

continued for our sake.

“It wasn’t hard to develop the styro/bovine

melding hormone that allows the animal to bulk up from foam. We let the

extension agencies in on the product without giving many details, just told

them it was a new thing. They’re used to new things that haven’t been fully

tested. Hundreds of years of registered pesticides that eventually turn into

monster chemicals that actually work against control, has these agents

operating beyond skepticism. It’s part of their makeup to overlook the

inevitable disaster and embrace the beast. It didn’t take them long to

disseminate the information to the local chieftains of ag. Orders for the

product came in the following spring. We were, of course, the only source for

the miracle diet product that was lighter than air to transport, fully absorbed

by the cattle, and totally reusable—remember, the stuff doesn’t break down at

all. Nowadays cows are probably 30% Styrofoam. Humans somewhat less. The death

industry folks had to be in on it, of course. We told them the same thing we

told the extension agents: just a new miracle diet thing. Collect up the

remains after the acidation of the corpses (cremation is out, of course; the

stack wouldn’t take the carcinogens created during incineration) and return it

to us for repackaging and reselling to the feedlots or any little startup

farmettes. Pretty neat, eh?”

Shelly and I said nothing.

“The stench and nuisance lawsuits went away.

Nitrogenous pollution and algal buildup in the water system went away. The food

shortages went away. The farm crises went away. The cancer went away. The

genius became rich.

I finally said something. “I don’t believe it.”

“It doesn’t matter. You don’t have to.

Makes no difference to me. My job is simply to keep the balance. To keep the

Styrofoam cycle static. What goes in, comes out and then goes back in. We can’t

make foam anymore, we can only use what we have on hand, what was vaulted up

last century. It’s all mined out now and distributed among the meat and the

people who eat the meat. The cycle is well documented and well monitored. We

can’t upset that now: we’ll end up with shortages again. Worse, the stockyard

and feedlot stench will return. You’re too young to remember how bad it was. It

was asphyxiating. Horrid. Sometimes you could actually taste the foulness in

the air. There is nothing in the world worse than a cloud of cow manure gas. I,

we, had to save the world from that.”

He seemed about to cry remembering the

trauma of odor. Who was I to argue? I had made a good living making sure that

sort of thing didn’t happen again but I remained incredulous.

“I don’t believe you,” I repeated, in spite

of the fact that I was beginning to like this strange little man.

“Me neither,” Shelly said.

Again the little man said, “you don’t have

to. I, we, could have ‘convinced’ you back at the clinic, but we needed to find

out who you were, what organization sent you. We needed time to organize your,

uh, acceptance of the explanation. Now I can proceed.”

Sometimes I remember what happened next.

Sometimes I don’t. I see Shelly in the hallway here on occasion. She can walk,

but she doesn’t recognize me. Neither of us can converse so I can’t confirm

with her what happened next.

I think what happened next was the little

man whipped out two desensor patches from the big pocket of his overcoat. It

happened so fast Shelly and I didn’t even see him slap them on the backs of our

hands.

When I woke up, I was here in a wheel

chair, barely functioning. I assume Shelly woke up in the lady’s wing, likewise

barely functioning. And here we have been for the last twenty years. Wherever

here is.

During all this time I have been living

inside my own head, retelling my story to anyone who would listen, in this

case, only me. I sit here with my blanket on my knees, Shelly’s sneakers still

hanging around my neck mocking me. The man, Dr. Chubb, gave them to me. Shelly

sits next to me, head lolling forward. She drools most of the day. Neither of

us is dead. We are both worse than dead; frozen, buried alive. Our minds race,

but we cannot move, cannot speak, cannot even look into each other’s eyes.

We are fed an injection twice a day to keep

us alive. No, not liquid Styrofoam, but some other miracle product that costs

little and keeps us awake and rapidly thinking. Why?

Buddy came and visited. Once. She sat down

next to me and explained about the last time we spoke. She hadn’t written down

what I’d said. Hadn’t followed through on the cease and desist, had merely

reported to the boss that I’d found some sort of dump site for plastic beads up

north. Next thing she’d heard is that both of us, Shelly and I, were in an

accident. She never found the load of white shit in the lockup. A team from upstate

cleaned up my mess on North Beach and took it away. To Jersey they said. She

was very, very sorry. She never came to visit again.

Friends came too, at first. But with no

conversation during the visits, it was a drag for them. Their visits tapered

off and finally they stopped coming altogether. At first I cared.

Here we’ve sat for twenty odd years. Our

nurses are never angry. Who would make them lose their tempers? Their charges

are all silently lolling and drooling. We never die or even age. I wonder if

each of us is retelling the same story in his or her own head.

Why do they keep us alive? We all wonder,

I’m sure, but I think I know why. One day the truth will come out. One day

someone will want to win an award for granting immortality to the human race

and he or she will need witnesses to their great triumph. They will want to be

immortalized. We will need to be shown

off. We will be their witnesses.

Or there’s some other equally cruel reason

for it.

I can’t wait until my prison term is over.

The first thing I’m going to do is expose this crap, this gulag archipelago.

I’ll denounce the whole damn effort, tell everyone it’s a lie. And I’ll kill

the bastard that started this Styrofoam thing. How I’ll find him I don’t know.

I used to think I could start with the strange little man, Chubb. He could have

helped me then, but he’s dead now. He committed suicide. It was on TV. I am not

sad.

I know why he killed himself: he felt

guilty. He knew it was evil to keep us alive and it was he who brought us here.

I saw the staff taking orders from him when he was still alive. I don’t know

exactly who Dr. Chubb was—if he was the mad genius or just a devoted fan—but he

was definitely a cheese. I heard the nurses talking the day after we saw the

news about him on TV the day after his suicide.

“What should the orders be now?” said one.

“Well, they haven’t changed after all these

years,” said his friend. “Might as well continue as before. He would have

wanted it that way. Just carry on.”

A

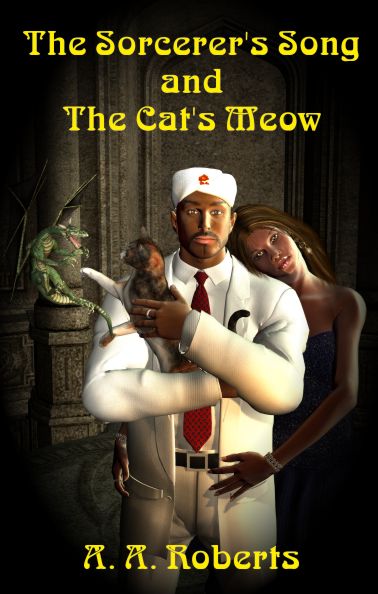

cat and her sorcerer, a beautiful dream weaver, an evil voodoo priest, a bunch

of man-sized rats, an army of really big bugs, a crazed randy rabbit, some dwarves,

dragons and angry three-toed sloths, New York City, the woods of Maine, the

sands of Arabia and the mythic lands of Avalon all come together for the

wildest most epic adventure you’ve ever read!!!!

A

cat and her sorcerer, a beautiful dream weaver, an evil voodoo priest, a bunch

of man-sized rats, an army of really big bugs, a crazed randy rabbit, some dwarves,

dragons and angry three-toed sloths, New York City, the woods of Maine, the

sands of Arabia and the mythic lands of Avalon all come together for the

wildest most epic adventure you’ve ever read!!!!

The Sorcerer's Song and The Cat's Meow is an author's triumph and a reader's delight... What a wonderful, free-falling storytelling ride to get to the end of a fantasy that's about as close to purrfect as you can get.

M. Wayne Cunningham - ForeWord CLARION Reviews

A well-plotted story with vivid and riveting description of characters and settings, as well as an intense page turning battle, the book is a delight to read.

Tracy Roberts - Write Field Services

Available in these

fine internet stores